LAUSD’s Academic Growth Over Time

When one searches “Aloria Magee” on Google, the second result is an LA Times page showing Magee’s “Los Angeles Teacher Ratings.”

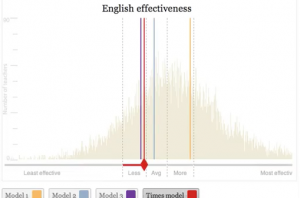

The page says nothing about Magee’s teaching style, nor her intense passion for the profession. But two large graphs appear, showing Magee’s “Math effectiveness” and “English effectiveness.”

Magee’s Math and English scores are both listed as below average, but a funny thing happens when the reader clicks on “See how this teacher would change under different statistical formulas.” Suddenly, Magee’s English score jumps to well above average when Model 1 is employed (one of four models shown on the graph).

Virtually no one except the LA Times wanted these scores released, including the superintendent, teachers, the teacher’s union and countless other stakeholders in education. Not only would it be a potential embarrassment to teachers and the district, but there was no guarantee that the scores would be reliable.

The Los Angeles Unified School District is now using a different, but similar type of model. AGT is a type of value-added model that aims to measure a teachers’ effectiveness, while controlling for various factors, such as socio-economic factors and starting student ability, factors that could otherwise compromise the results.

Although the initiative is still in its pilot phase, slightly more than half of the district’s teachers currently receive their scores every year, according to LAUSD’s Director of Performance Management, Noah Bookman.

The district is working with the University of Wisconsin, to develop their measures for AGT. The school received a $2 million grant to help the district craft a formula for teacher effectiveness.

“Academic Growth Over Time is a measure of how a teacher or a school contributes to student outcomes,” explained Bookman. “Different how from how we usually measure student outcomes, which is we measure how kids do against a specific standard like the percent of students who are proficient, Academic Growth Over Time allows us to compare teachers or schools to another in terms of how they do in taking students from Point A to Point B.”

The district essentially hopes to determine teacher effectiveness by following the students’ scores from year to year. The district argues that this method prevents the results from being skewed if a teacher works in a low-income neighborhood, for instance.

Instead, AGT analyzes what happened to each student’s test score when the student was in that specific teacher’s class. Did the girl’s scores improve? Did they regress? Did her standardized test scores stay the same?

Various teachers, however, are not convinced of the district’s logic about the validity of AGT. Neither is the teacher’s union, United Teachers of Los Angeles.

UTLA representative and former teacher Susie Chow does not believe something as complex as teacher effectiveness should even be partially measured by standardized test scores.

“LAUSD or the powers that be want to use a real simple, supposedly effective, data-driven method, but they’re not considering all the other factors that come into teaching,” said Chow.

“We’re working with human beings, people that are going through divorce in their family or are not motivated to take their test that day or having issues with their video games.

“So we’re dealing with human beings so to try and simplify somebody’s effectiveness to one test score is ridiculous.”

First grade teacher Nellie Kerr has taught at Serrania Avenue Elementary School for 13 years. Although she does not receive AGT scores because first graders do not yet take state testing, she does not think AGT is a fair method for the district to use to evaluate teachers.

“What could get hard is that there’s a lot more to a child and what’s going in their life than what’s going on in the classroom,” said Kerr. “So therefore maybe a child does very well one year, they don’t do as well next year. What happened in their life? Was there a divorce? Was there a move? Was there a death in the family? Were there things of that sort that affected the child?”

“Where a child comes from every single day, if they’ve eaten breakfast, how they feel that morning, if they’re sick, all that has definite factors on how they’re going to do on a test,” said Magee.

“And a teacher shouldn’t be graded based on how a particular kid has done just because you don’t know if they got yelled at before they came to school.

“We don’t know what’s going on and to judge us for that is not fair.”

When the LA Times computed and publically released teacher effectiveness scores in 2010 and 2011, it used a value-added formula similar to what LAUSD now uses with AGT.

Tragically, Rigoberto Ruelas, a fifth grade teacher at Miramonte Elementary School, committed suicide as a result of what his family called depression about his effectiveness rating.

Although Ruelas was rated by the LA Times as slightly “less effective” than his peers, then-UTLA President A.J. Duffy said, “Despite The Times’ analysis and all other measures, this was a really good teacher.” Although LAUSD would like to keep AGT scores confidential, Chow and Janet Davis, who works in the Teacher Support Unit of LAUSD, said that the whole LA Times fiasco upset many teachers, even some of those who received good rankings.

Kerr is also concerned by another factor she believes the district has ignored.

“We’re not really taking into consideration child development and that children do progress at different rates,” said Kerr. “You can’t really take a slice out of a child’s life or a test score out of a child’s life and judge a child by that, let alone the teacher they happen to have that year.

There is also concern regarding the reliability of a teacher’s AGT score. In July of 2010, the U.S Department of Education found that “value-added models applied to student test score gain data” are likely to be wrong approximately 25 percent of the time when three years of data are used.

UTLA Secretary David Lyell has worked tirelessly to raise awareness on this margin for error issue. “25 percent of the time an effective teacher is going to be rated as ineffective and 25 percent of the time an ineffective teacher is going to be rated as effective,” said Lyell.

“So no matter what job you have, imagine it this way: Where your employer says, ‘Ok. We’re going to rate you according to a system that 25 percent of the time is inaccurate,’ so it’s really a poor model.”

Bookman said the study did not exactly find that AGT-like measures were wrong 25 percent of the time. “Actually what they found was 25 percent of the teachers (that) categorized as above average one year were below the next year,” said Bookman.

According to Bookman, LAUSD does not provide AGT scores when they are not confident of the results.

“We’re very transparent about our level of confidence in the result that we provide for a particular teacher,” said Bookman. “So we don’t, for instance, categorize a specific teacher’s results as above or below average unless we have a 97 percent confidence that that’s accurate.”

“What’s an acceptable rate of error when your job’s on the line?,” asked Lyell. “For me, 25 percent is too much.”

Presently, teachers’ jobs are not on the line regarding their AGT scores, as the initiative remains in its pilot phase, but Lyell asks a legitimate question.

Presently, teachers’ jobs are not on the line regarding their AGT scores, as the initiative remains in its pilot phase, but Lyell asks a legitimate question.

LAUSD claimed that AGT scores are significantly more reliable than the U.S. Department of Education’s study found general value-added models to be.

“In our district, less than 1 percent of the teachers using their three-year Academic Growth Over Time (results) were rated as above average one year and then the next year their three-year results were below average,” said Bookman. “And even if we look at their one-year AGT over time, I think it’s less than 6 percent would’ve been on this one measure as below average one year and the above average the next.”

Davis is not convinced.

“The biggest part, which even the district and the superintendent have said, is the sample size is so small and there’s so much noise,” said Davis. “If you have a little bit of the flu going around your classroom or whatever, your test results are skewed by very small things, because the sample size is too small.”

Davis is also worried that using AGT to rate teacher effectiveness (even in its pilot phase) has increased the incidence of what teachers call “teaching to the test,” a phenomenon where teachers craft their lesson plans purely according to whatever will maximize student performance on standardized tests without regard for actual improvement in critical thinking skills.

Davis’ son went to an elementary school that “taught to the test,” according to Davis. Because the school was so focused on test score gains, Davis’ son exclusively took multiple-choice tests, which she argues was the least valid test for students with learning disabilities like her son.

“If you become a test-obsessed school, you’re destroying the students,” said Davis.

In contrast, Vivian Cordoba, principal of Enadia Way Elementary School in West Hills, thinks “teaching to the test” can be an effective tool. “As long as we have the standards, that’s what our star test is, the C.S.T.s (California Standards Test).”

“They’re based on the standards,” said Cordoba. “So if you’re teaching to the standards, you’re teaching to the test. Right?”

For Kerr, “It will take any creativity out of the curriculum, and you’ll basically get teachers drilling students to make the right answers on a test.”

“It will take critical thinking out,” added Kerr. “It will take exploration out. It will take investigation out.”

Many elementary school teachers like to work collaboratively by “team-teaching.” This involves swapping students for various subjects, typically based on the teachers’ strengths and weaknesses.

Many elementary school teachers like to work collaboratively by “team-teaching.” This involves swapping students for various subjects, typically based on the teachers’ strengths and weaknesses.

For instance, a teacher may send her students next-door for language arts and social studies, while agreeing to take his neighbor’s students for math and science, subjects which he knows best. Because every elementary school student only has one “teacher of record,” some are concerned that use of AGT scores will inhibit teacher collaboration.

Magee teaches math and science to a new set of students from 11 am to 2:40, but the kids’ 8 am teacher is linked to their math scores even though Magee is technically teaching them math. “I’m here, but they only put her name down, so if they were going to base it on test scores, then of course she would get the high test score and I would have no score at all,” said Magee.

“It is not possible to disaggregate the scores and when you try to do that, you’re disincentivizing the very thing you want, which is collaboration,” said Davis.

“If we’re team-teaching on different subjects, who gets the score?” asked Chow.

The district admits that it does not yet have a solution to this problem, but it claims it is exploring possibilities.

“Ensuring that we have accurate student-teacher linkages is what it’s called, so are we attaching the right teacher to the right set of students in order to have an accurate measure,” said Bookman. “There are some options out there that have proven to be pretty useful in other districts and other states, but at this stage, we have not gone beyond using the information that comes out of our data systems.”

“There’s very little evidence that we’re aware of that would suggest that providing teachers with useful tools and useful information actually deters teachers from working together,” said Bookman. “That’s more of a school culture issue.”

Kerr agreed that AGT scores would likely not inhibit team-teaching. “I think if you were going to collaborate with another teacher, you’d probably pick somebody that had close to your teaching style and somebody that you felt comfortable with,” said Kerr.

Chow argued that assigning AGT scores using the “teacher of record” method would only fuel unhealthy competition and increase the desire for teachers to hoard effective teaching techniques.

“If you see a doctor, you would want your doctor to collaborate with other doctors because you want the best health care that you can get,” said Chow.

“Well that’s what we encourage for teachers.

“We don’t want them dividing.”

Although the district claims that it understands that AGT can only tell part of the story of a teacher’s effectiveness, some teachers along with UTLA fear that AGT will be used increasingly at the expense of other evaluation methods they believe to be more effective.

“When UTLA was having informal conversations with the district, we were referring to what would become Academic Growth Over Time as multiple measures, which might include test scores of some kind, but would (also) include work samples, writing samples, portfolio assessments (and) all kinds of other assessments,” said Davis. “When they decided to window dress VAM (value-added models), they took the name AGT and changed it.”

“I’ve asked them if they mean to add other things and they say, ‘Oh yes, yes, yes,’ but as of yet, nothing else has been added, but they’ve just taken the test scores and put them through the formula,” said Davis.

“Most of our effort as a system has been focused on how we do the key element of performance review for teachers, which is observational practice,” assured Bookman. “So the main way that teachers are now and will be evaluated in the future and helped to improve their practice is when a well-trained expert observer goes into a teacher’s classroom and observes what a teacher’s doing and provides them feedback about that.”

Bookman repeatedly claimed that there are “no stakes” in AGT’s pilot phase. Despite Bookman’s claim, some teachers have already been ridiculed for low scores.

“We do know of one school where the principal was calling teachers in at the beginning of the school year and saying, ‘Well, I see you had a low rating so what do you plan to do? And if you don’t do better, I suggest you might want to transfer to a different school,’ so there’s those kinds of threats already.”

Chow cited a middle school where the principal also called in teachers and scolded them regarding their AGT scores.

“We provided very explicit guidance to our administrators this year about the appropriate and inappropriate uses of AGT at this stage,” said Bookman. “And at this stage, that guidance included (that) it should be used for professional growth. It should not yet be used for evaluation.”

Even though LAUSD does not condone such behavior from administrators, Chow is not surprised that principals would act this way given the importance the district seems to placing on AGT.

Davis and Chow do not believe test scores should be factored in when determining teacher effectiveness. Rather, they argue teachers should be evaluated by the National Boards for Professional Teaching Standards.

This method involves teacher submission of portfolio work, teaching videos and an essay section where teachers are asked to explain their accomplishments. There are ten parts of the evaluation, all of which are independently scored by “calibrated assessors,” according to Chow.

Davis and Chow argue that this multiple-factor approach is what’s sorely missing from the current AGT method.

Lyell believes the district’s intense focus on teacher effectiveness is missing the point.

“The bottom line for me is that we’re hyper-focused on teacher effectiveness to the exclusion of all other factors of teaching, which is extremely complex,” said Lyell. “We need to start looking at class size and how we can start celebrating what teachers do rather than the current climate of let’s fire our way to success.”

Lyell recommended lower class size and increasing California’s financial investment in education.

Lyell also stressed the importance of “thinking of teachers as the solution rather than the problem.” He added, “We need to stop this demonization of teachers.”

Cordoba said she would support AGT, but with qualification: “The benefit of this, if they get it right (is) I would see this as another tool.” Cordoba also recommended introducing teacher report cards, because she argued that students’ performance is significantly influenced by their environment at home.

Similarly, Kerr recommended that parents be increasingly encouraged to participate in their child’s education at home, but also asked to visit the teacher more often.

“I would definitely put more money back into the schools,” said Magee.

For Magee, cutting class size is also something that must be done.